On September 5, 2025, China's first space-based film, "Blue Planet Outside the Window," hit theaters nationwide. As the screen lit up, the Chinese space station, 400 kilometers away, seemed to instantly draw closer. The 8K camera's lens swept across the snow-capped Qinghai-Tibet Plateau and the coastline of the Liaodong Peninsula, the folds of the Taklamakan Desert, and the brilliance of the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei urban agglomeration. Every frame told the same truth:

All the magnificent mountains and rivers on this blue planet are our common home. These images are not only shocking but also full of scientific value. And the space seen from the perspective of astronauts gives the film a real and moving sense of presence.

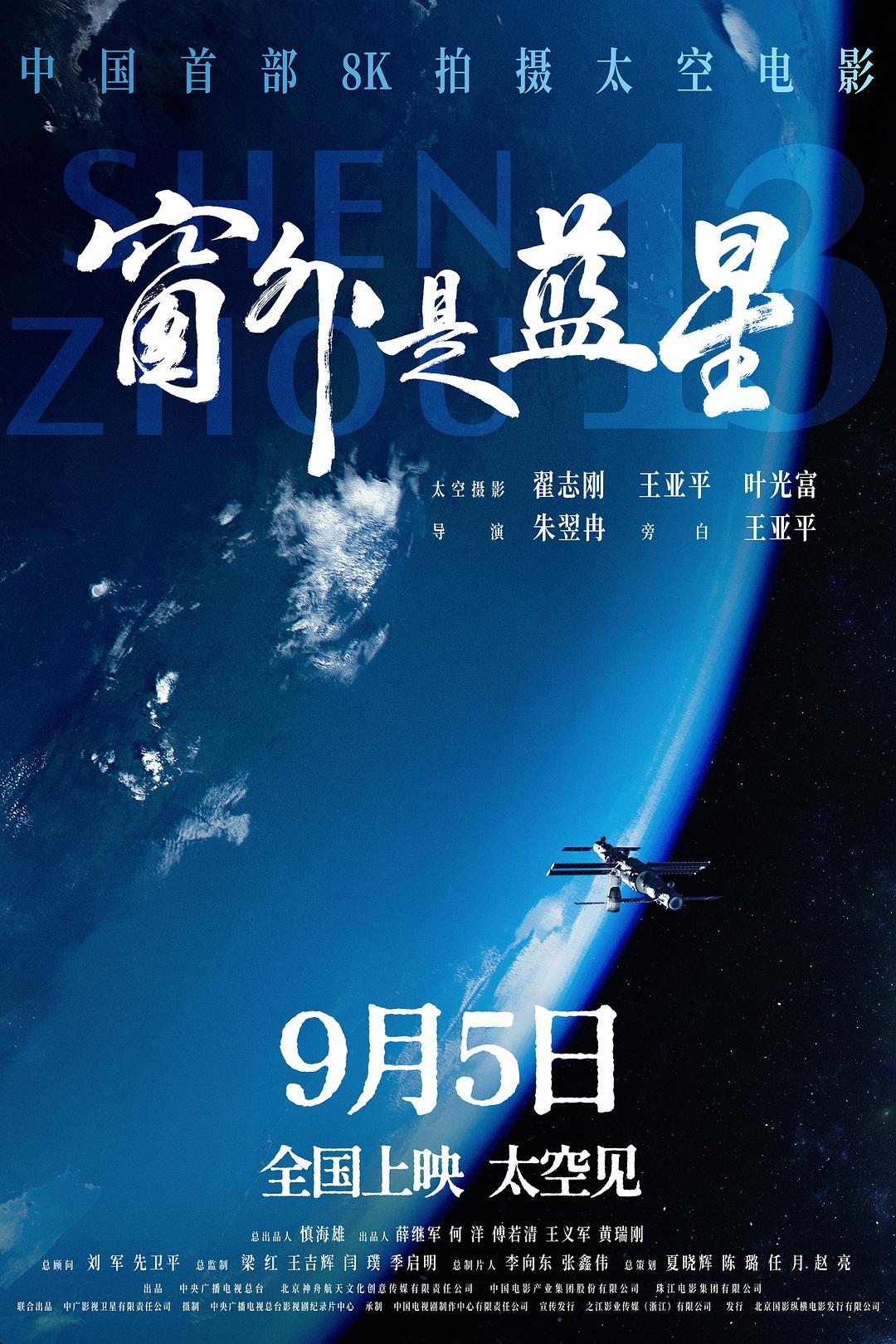

Poster of "Blue Star Outside the Window"

The filming of "Outside the Window, Blue Planet" was a breakthrough for both astronauts and filmmakers. Astronauts doubled as "space photographers," using specially designed domestic 8K cameras to record the Shenzhou 13 crew's 183 days and nights in space, in addition to their demanding scientific research. While the creative team couldn't set foot in space, they relied on specialized space-adapted equipment and remote collaboration with the astronauts to transform the "distant expanse" into a "touchable everyday experience."

In this immersive space journey that feels like being in a space station, the audience will not feel like they are "watching a movie", but rather like following the three astronauts Zhai Zhigang, Wang Yaping and Ye Guangfu, and experiencing a space stay lasting several months.

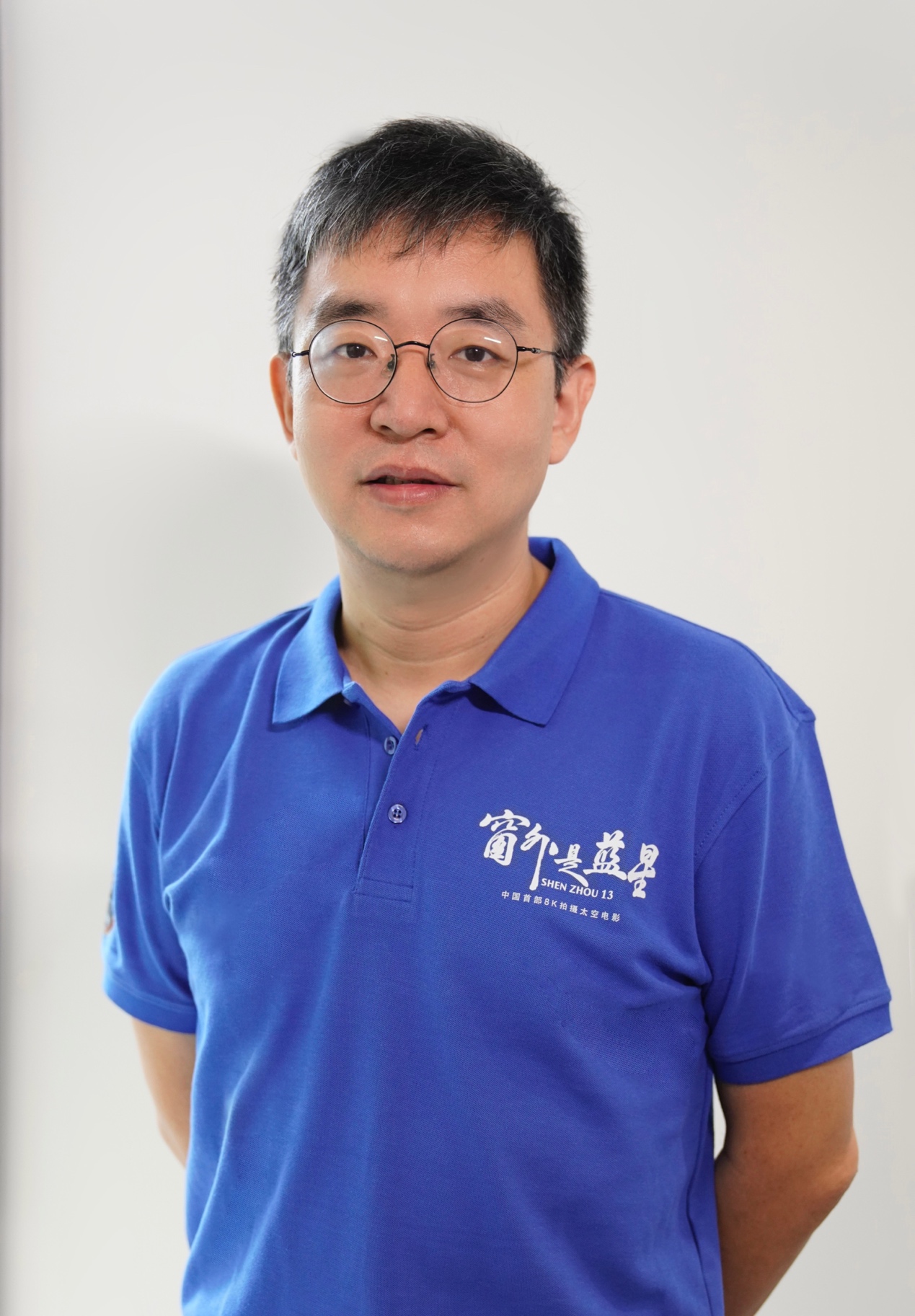

Before the film was released, director Zhu Yiran gave an exclusive interview to a reporter from The Paper, leading readers to feel the warmth of a great power's powerful weapon and touch the romance deep in the universe.

Director Zhu Yiran

The camera that almost couldn't catch up with the rocket and the director who couldn't fly

"In fact, long before we started preparing, the world's major space powers had already set their sights on the field of 'space movies'."

When the team just came up with the idea in 2021, they found out about the developments of many peers: Cobus's team had planned to go to the International Space Station to shoot a feature film, French astronauts had already filmed "16 Sunrises" on the space station, and Russia even sent photographers to do special space flight training for the movie "Challenge"... "At that time, I felt that space was going to become a new arena for the film and television industry, but there was a hard threshold for this - it had to rely on manned space technology, and not everyone who wanted to do it could do it." Zhu Yiran said.

At that time, China's space program was at a critical juncture. In 2021, China was preparing to launch the core module of the space station, a crucial requirement for space filming. "Previously, Yang Liwei and his colleagues flew into space, but their short time in orbit and limited space meant they couldn't film. But with the space station, with its long-term presence and stable operations, we now have the potential to create films and television shows." The CCTV team keenly seized this opportunity. "Previous reports on Chinese people flying to, staying in, and exploring space have become a familiar, fixed formula. We wondered if we could break away from this context and explore new expressions within the realms of 'space literature' and 'space news propaganda.'"

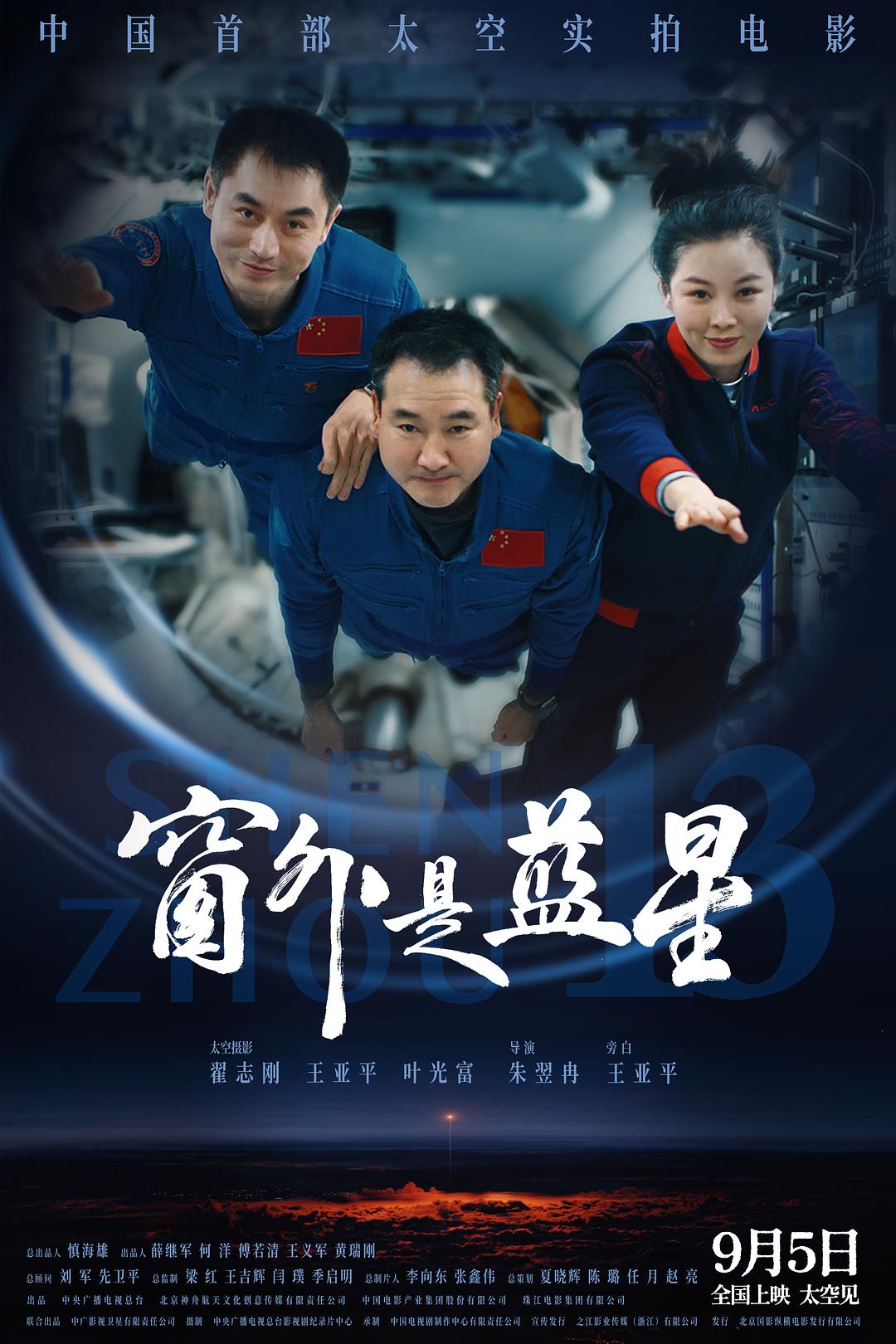

Stills from "Blue Star Outside the Window"

The first step in filming a "space movie" was to find the right equipment—ordinary cameras were simply unsuitable for the space station's working environment. "The machine would float in a weightless environment, the vibrations during launch could shake parts apart, the charging standards had to be aligned, there had to be no odors in the space station, and no interference with scientific research equipment, among other criteria." Zhu Yiran approached seven top domestic film and television equipment companies and collaborated with the aerospace team on a single goal: to adapt the 8K movie camera. The size, power supply, and operating methods of traditional cameras didn't meet the requirements for space filming. They disassembled and reassembled the cameras, replacing batch after batch of parts. After more than six months of hard work, the four cameras were finally reduced to the size of "three cargo bags."

Astronauts are limited in what they can carry into space. Even the small bunny pendant they carry with them in the film was a space Wang Yaping squeezed out after repeated calculations. Inside the space station, astronauts are tasked with carrying out a range of scientific research tasks, so filming documentary footage isn't a high priority. Therefore, for a long time, the question of whether the "three suitcases" could ultimately make it onto the cargo ship carrying the subsequent supplies was a heavy concern for Zhu Yiran.

There was a small incident before the camera was launched. Initially, the team focused on developing the camera itself and neglected the packaging. As a result, an odor was detected in the backpack before it was put on the spacecraft, and the space station absolutely does not allow any foreign odors. At that time, there were only a few days left before the launch of the cargo spacecraft. Zhu Yiran was so anxious that he contacted the factory overnight to redo the cargo bag. "The workers worked around the clock. After they finished, we sent someone to carry the cargo bag and take the fastest flight to the launch site. After rushing all the way, we finally caught up with the rocket."

The entire space shoot was conducted in 8K 50fps. The higher definition meant these precious footage was incredibly memory-intensive. A 1TB card could only hold just over ten minutes of footage. The original plan was to prepare 50 frames, but the equipment manufacturer scoured their inventory and could only muster 40. "The rocket couldn't wait, so we had to send these 40 frames up first. We repeatedly reminded the astronauts to use them sparingly—for example, this scene could only be operated for 10 to 15 minutes, that shot could only use one card, and even if it wasn't perfect, there was no re-shooting."

Difficulties like these abound, and every operation that's routine on Earth becomes difficult and a luxury in space. "When the camera successfully reaches the space station, we've at least taken the first step toward success," said Zhu Yiran.

Special space camera

Zhu Yiran, a documentary director at the CCTV Film and Television Documentary Center, has worked on a number of high-scoring documentaries, including "Aerial China." This particular shoot was particularly unique in his career. Not only was he unable to attend the scene, but his communication with the photographers was also extremely limited. "I was the only director who had to watch the TV news to see when my crew was working."

Without on-site direction, emails became the only "shooting guide." Zhu Yiran divided the mission into a "customized checklist" and "free creative work." On the one hand, he worried about the limited capacity of the footage cards, and that the astronauts wouldn't be able to shoot quickly enough to capture the excitement. On the other hand, he worried that the heavy workload of scientific research would leave insufficient time for filming and insufficient footage to support a full film. It wasn't until the Spring Festival holiday that he saw footage of the space station's interior on the news and immediately recognized the cameras mounted on the wall. At that moment, his anxiety finally settled.

When the space footage returned to Earth, the editor couldn't wait to insert the card into the machine. The first shot deeply moved Zhu Yiran: the blue planet slowly turning in the background. Without narration, it spoke volumes. "I think the Chinese astronauts demonstrated tremendous cultural creativity and personal charisma in this film. I'm truly impressed by them."

From a national hero to an ordinary person on the screen

In October 2021, before the Shenzhou-13 crew departed for space, Zhu Yiran conducted a three-hour face-to-face training session with astronauts Zhai Zhigang, Wang Yaping, and Ye Guangfu. Teaching astronauts photography was a "mission," and in addition to the Shenzhou-13 crew, the subsequent Shenzhou-14 and -15 crews, including the already returned Shenzhou-12 crew, also participated in the training.

Operating a camera is not a difficult task for astronauts, who need to control many complex equipment and instruments. Most of the time, "we don't talk about 'how to shoot', but 'what to shoot'."

Poster of "Blue Star Outside the Window"

Unable to track the filming progress in real time, Zhu Yiran admitted that he was initially apprehensive. "I was particularly worried that they would film the scene saying, 'Hello everyone, I'm currently at the Chinese Space Station...'" Zhu Yiran repeatedly emphasized to the astronauts, "In previous reports, you were portrayed as heroes for the entire nation. But in this film, I hope you'll be portrayed as warm, living people."

So in the movie, we see three ordinary people living in space: they devour special space food in various ways, they sort out supplies while floating in a weightless environment, their eyes turn red while talking to their children on the phone, and they stare blankly at the window...

"So after watching the film, many viewers felt that we didn't exaggerate or emphasize anything. We simply told the story in a plain and simple way, just like living life. That's the effect we wanted to achieve."

The three astronauts each possessed distinct personalities, their occasional displays of humor endearing and heartwarming. Zhai Zhigang possesses beautiful calligraphy, including the large characters that create the film's title, "Outside the Window is a Blue Star." Wang Yaping's science lectures were particularly engaging and lively, while Ye Guangfu's Hulusi playing was also captivating.

Ultimately, the film was reassembled based on the returned footage, with female astronaut Wang Yaping serving as the narrator of the space flight. "Only someone who has been to space can truly convey that immersive feeling of space travel through narration." She is an astronaut, a teacher, a mother, and a daughter, and these multiple identities bring richer emotional layers. "I wanted the film to have more tenderness, and a female perspective perfectly complements that."

Wang Yaping

In the film, Wang Yaping recounts a letter she received from a female American astronaut before her departure, telling her that countless women around the world, because of her, have also set their sights on the distant horizon. Her calm, yet slightly hoarse, voiceover is particularly powerful and moving. Director Zhu Yiran reveals that the hoarseness stems from the fact that her unit only gave her one day to hone her voice, repeatedly working from morning till night, which honed her voice and gave it its unique texture.

The footage also contains many moments that surprised Zhu Yiran, such as a shot of Ye Guangfu talking to his family: he sits in the call center, his wife smiles on the other end of the screen, while his little daughter runs around restlessly, suddenly leaning her little head towards the camera and calling out "Daddy" in a baby voice. The space station is a major national artifact, but the appearance of this little head imbues the cold technology with the warmth of home. And then there's the pink bunny stuffed animal that Wang Yaping brought into space, floating gently in the weightless environment, like a symbol of affection: no matter how far you fly, the thoughts of home are always there.

"As a director, I was pleasantly surprised by many shots I saw. This surprise wasn't necessarily about how well a particular shot was taken, but rather that they completely understood what I wanted and the temperament that the film was meant to portray."

Stills from "Blue Star Outside the Window"

A space journey, a seed

To condense a six-month space stay into a 90-minute film, the creative team chose an immersive "space journey" in their editing strategy. There's no deliberate science explanation, just a glimpse into the astronauts' daily lives.

The narrative structure is designed entirely according to "human senses." Upon entering the space station, the first thing to film is "how to survive"—where does water come from? How do you eat space food? How do you secure your sleeping bag? How do you get oxygen? These most basic survival details are everyone's first reaction to arriving in an unfamiliar environment. "It's like when you arrive in a new place, your first reaction is to settle down and solve the problem of survival, rather than enjoying the scenery first. Once the survival problem is solved, you can then film getting down to work and completing the most difficult tasks. Only then will you have the time to lean against the window to admire the scenery, think, and slowly feel nostalgic, and finally return home with reluctance and anticipation."

Stills from "Blue Star Outside the Window"

The Chinese space station inherently promotes science. Entering that environment from the astronauts' perspective naturally puts you in a classroom filled with space knowledge. Popularizing science is a natural outcome, but the team intentionally avoided overemphasizing "knowledge points." "We didn't deliberately try to popularize science because we don't want audiences to go to the cinema and feel like they're attending a 'class.' That's not what the film is about."

Some viewers also asked, "Why does the movie end as soon as the spacecraft lands?" Zhu Yiran's answer was clear: "Because the space journey is over—how they exit the spacecraft, how they embrace their families, is their personal matter. The space journey ends the moment they land. We wanted to maximize the concept of 'space travel' and let the audience remember the real time in the space station."

On a deeper level, it's about the transmission of culture and emotion: "There's a line in the film, 'No matter how far we fly, celebrating the Chinese New Year is the most important thing for Chinese people.' This is the core of what I want to express - science will take us further and further, and perhaps one day we will no longer be on Earth, but the cultural traditions of the Chinese nation, the cultural genes in our blood, our attitudes and our values will continue and will not change even if we fly further."

Stills from "Blue Star Outside the Window"

The significance of this film goes far beyond presenting a journey. "I hope it can be a catalyst," Zhu Yiran said. For children, it may be a "seed" that will make more children interested in aerospace and feel that space is not a distant "high-tech field" but a place related to people's lives and emotions. "In the past, everyone thought that space was very far away and very 'high-tech', but this movie has details about the astronauts' food, accommodation and transportation, and their interactions with their families, which can make children feel that space is not out of reach." At the same time, this filming will also allow Chinese film and television to further explore more possibilities for real-life space shooting, "which will play a role in promoting the creation of future feature films and documentaries."

Premiere

This is a film about dreams. "The road is long and winding, when will the fruit be found? My heart's desire is my trust..." As the ending theme song "Prosperous Galaxy" from the film "Outside the Window is a Blue Star" slowly plays, scenes flash across the screen, a true portrayal of the meticulous efforts of China's manned spaceflight team—from preliminary explorations in the 1970s to the official launch of the China Manned Space Program in 1992; from Yang Liwei's display of the national flag in the space capsule during his maiden flight of Shenzhou V, to the astronauts of Shenzhou XIII setting a new Chinese record by remaining in orbit for six months... Chinese astronauts continue to run the relay, constantly creating new space achievements.

Each shot transition represents a leap forward in time, not simply a technological iteration, but a generational, all-consuming pursuit of a dream. This is the history of China's space program, and even more so, a microcosm of a great era. At the premiere, Zhu Yiran lamented that the perfect timing, location, and people made it possible for them to "make this film at this moment in time."

"120 years ago, China filmed the first documentary film, 'Dingjun Mountain.' 120 years later, Chinese films are also using the camera to focus on our Earth. I think this is a star picked up from space by China Aerospace and China Central Radio and Television. This star is a gift to all people with dreams."