Cao Baoping is a highly respected director in the Chinese film industry, known for his sharp subject matter, powerful style, and masterful ability to tame audience emotions. His previous works, such as "The Burning Sun," "Dog Thirteen," and "Wade the Sea of Rage," all trudge through the complexities of human nature and social realities, using a sharp perspective to analyze the cruelty of life and the subtleties of human nature, constructing a unique "Cao aesthetic" system. However, his new work, "The Runaway," a new entry in his "The Runaway" series, seems to have gone too far.

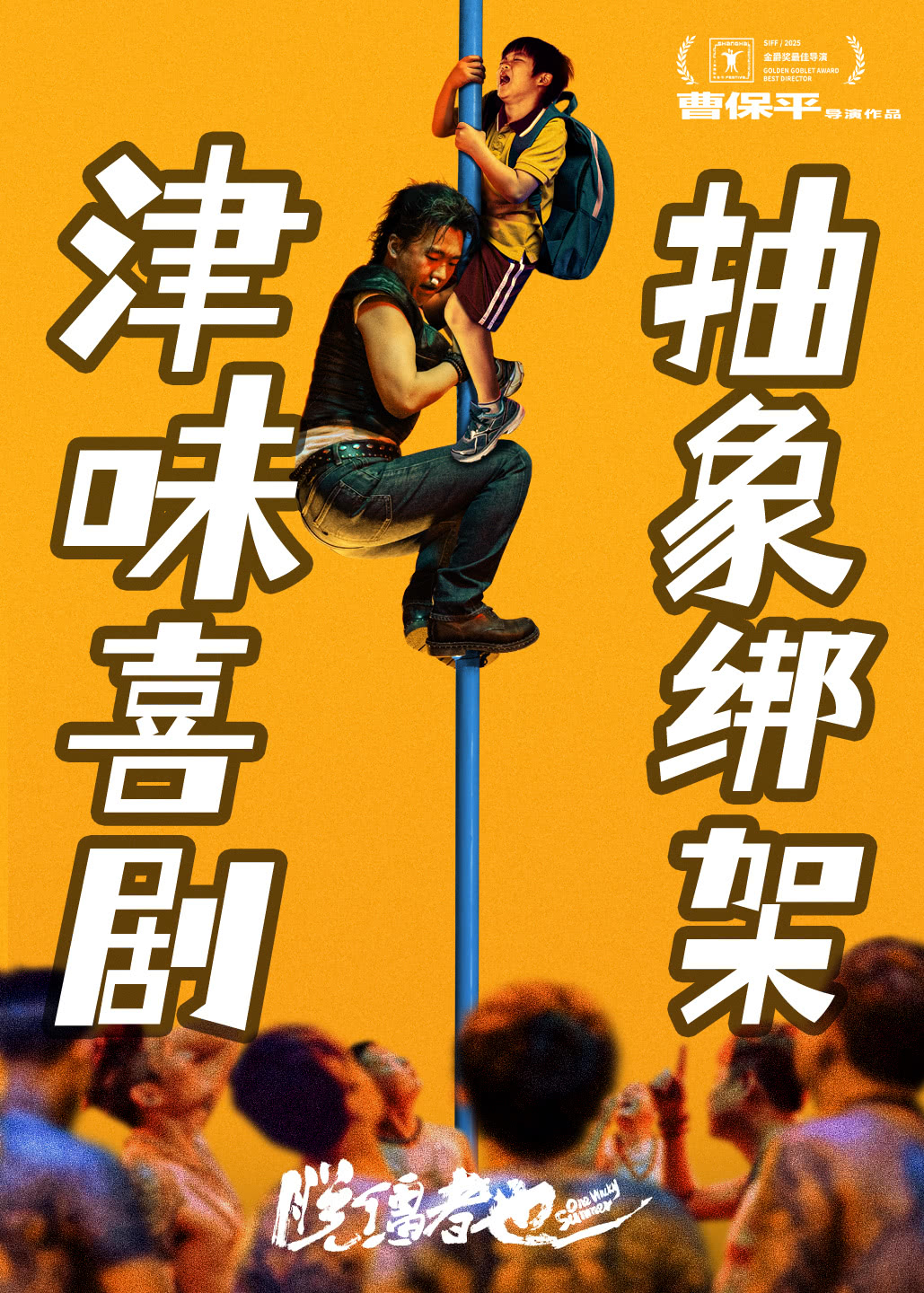

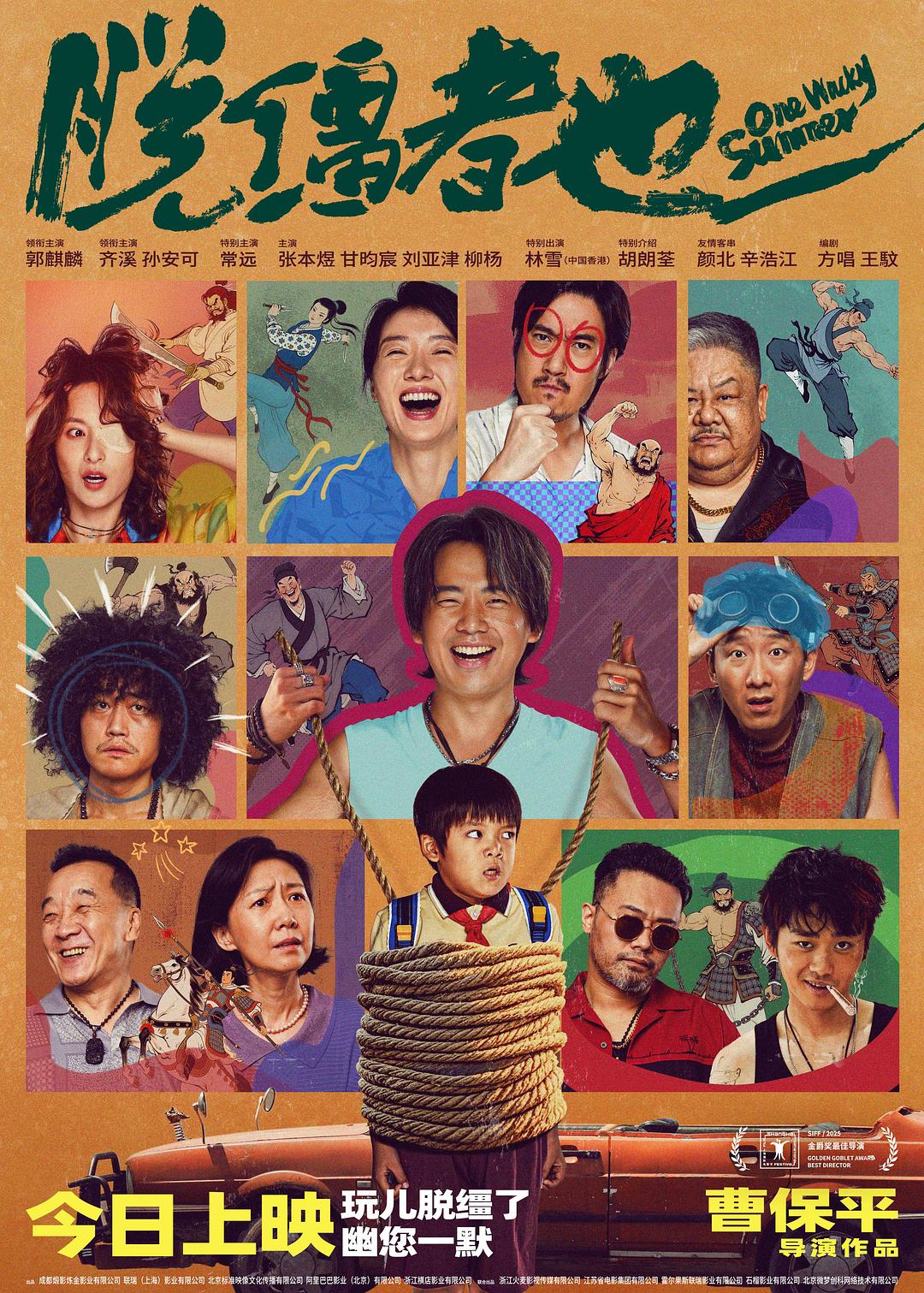

Poster of "The Runaway"

Lead actor Guo Qilin's Tianjin dialect is authentic, but movies aren't crosstalk; it's not about getting the dialect right that makes the characters and story work, that makes people empathize and identify. "The Runaway" is lively enough, with its hilarious banter, but this veteran actor seems to have stumbled upon the wrong gate of Tianjin, and the resulting drama is like a pancake with the wrong sauce: tempting to look at, but the flavor is off, and swallowing it is a pain in the ass.

The plot of "The Runaway" is as captivating as the protagonist, Ma Fei, is. As the title suggests, the protagonist is like a horse on the loose, driven by the trauma and resentment of his family. He uses clumsy attempts to resist, but ultimately loses control. Ma Fei, an uncle, is a "naughty child" at heart. He takes his nephew on a hilarious adventure. Along with several other equally unreliable adults, this absurd "runaway journey" gradually uncovers the emotional scars behind each character. In the film, Ma Fei, trapped in a state of "immature youth" due to the lack of love in his upbringing, attempts to fill this inner void with absurd methods. His kidnapped nephew, though young, unexpectedly becomes a mirror reflecting the absurdities of the adult world through his innocent childlike perspective.

Guo Qilin as Ma Fei

The dialogue is characterized by the Tianjin dialect, skillfully blending black humor with Western elements. The "runaways" traverse the unique landscapes of Tianjin's Dagang port, including its oil fields and salt pans, forging unexpected bonds amidst the urban life. Through interludes of Tianjin-infused banter, Cao Baoping's signature multi-threaded narrative peels back the layers of noir crime to uncover the often-overlooked emotional bonds of family.

Family portraits in movies

The film's core conflict revolves around the fierce competition among the three siblings of the Ma family over the family's demolition compensation. Ma Fei, a seemingly idle individual, is determined to secure this enormous sum. The eldest sister, a devoted brother-supporting woman, sees her younger brother, Ma Fei, as the one to be protected and cherished. Meanwhile, the second sister, Ma Hui, maintains control of the family through rational calculation and consideration. Fearing that her brother might stray from the path of the money, she firmly refuses to share it. Driven by frustration and impulsiveness, Ma Fei personally orchestrates and executes the kidnapping of his second sister's child, Li Jiawen.

The first half of the film creates dense laughter with the repeated out-of-control of the "kidnapping plan": Ma Fei and his nephew Li Jiawen are on the so-called "escape", and the nephew repeatedly escapes cleverly, but is recaptured again and again; the gangsters' pursuit is full of hilarious problems; there is even a "one-eyed stewardess girlfriend incident" caused by a misunderstanding of dialect, and the plot develops unexpectedly absurdly.

Ma Fei and his nephew, Li Jiawen, two generations of "naughty children" in the family, serve as both kidnapper and victim in this farce, yet also strangely mirror each other. Both Li Jiawen and Ma Fei engage in behavior typically considered "bad" by the adult world, openly challenging family authority. While the two men's seemingly "rebellious" behavior, such as letting the children drive during the "kidnapping," is in reality a form of compensation and catharsis for Ma Fei's own childhood deprivation. That wasn't a steering wheel; it was the "voice" Ma Fei had never had before. In this family, he was forever the "immature younger brother" and the "unreliable uncle." Only this absurd "kidnapping" could allow him to temporarily regain his position as the "man in charge."

The kidnapped nephew

The father figure, who never appears directly in the film, looms like a ghost over the family, becoming the root of their trauma. Ma Fei's emotions towards his father are complex and tangled. He yearns for his father's approval and love, while also harboring deep resentment for past hurts. This conflicting emotion becomes the core internal motivation that drives his series of unbridled behaviors.

The characters in Cao Baoping's past films are mostly "stubborn individuals" brutally tormented by fate and social norms. They struggle and resist in difficult situations, confronting the world with an almost paranoid attitude. As the saying goes, "unfortunate people use their lives to heal their childhoods," Cao Baoping seems to be perpetually making films with the same theme, sharing the same pain and depicting a diverse range of characters shaped by the same underlying causes.

Li Wan in "Dog Thirteen" is repressed by his East Asian patriarchal family and constantly struggles as he grows up, using stubbornness and resistance to find his true self. The father and daughter in "Crossing the Sea" become increasingly lost in their love-hate relationship, ultimately losing control. Through Cao Baoping's lens, we delight in witnessing the rough textures of life and the multifaceted complexity of human nature, revealed by conditions pushed to the extreme.

In "The Runaway," however, the characters become thin and stereotyped. Ma Fei, the "wild uncle," appears to be a down-and-out young man struggling at the bottom of society, attempting to change his fate by kidnapping his nephew for demolition compensation. However, his motivations and characterization are purely that of a "naughty child" who gets his way. He acts relentlessly in the early stages, then abruptly achieves self-redemption at the end. His relationship with his nephew, Li Jiawen, is overly absurd and fails to establish a convincing emotional bond. It's difficult for the audience to feel a deep emotional resonance from their interactions, let alone appreciate the profound influence of their original families on their personalities and destinies.

Not only is Ma Fei's sudden transformation from his early, unruly behavior to the finale unconvincing, but Qi Xi's transformation from assertive to overbearing second sister is also abrupt and contrived. As for the underworld clues from eldest brother Lin Xue, they're just the stereotypical "stupid thief" tool, acting ruthlessly and foolishly, with a lack of humor that makes you want to ask, "What the hell is he doing?"

Movie stills

At this year's Shanghai Film Festival, Cao Baoping said he wanted to make something "different." This time, he's indeed different. On the surface, the difference is more lively, with a higher proportion of comedy and absurdity. His aura is less austere, and with the influence of Tianjin's local culture, the film's pervasive "what the hell" and "don't bother" feel more relaxed and uninhibited. In terms of style, this director is indeed constantly expanding his horizons. The Shanghai Film Festival's Best Director award this year is a testament to his creative prowess.

In my opinion, the deeper difference is a kind of "laziness" in motivation. Cao Baoping is not "painful" this time, and the addition of Guo Qilin seems to have shifted the focus of the creation to the "high" of Tianjin dialect: the criminal plot has become a foil to the family farce, which is boring; the family tragedy is projected onto the absurd behavior of the giant baby, which is boring.